A Barnstaple Poisoning

A True Account of a Victorian Tragedy

A Barnstaple Poisoning

A True Account of a Victorian Tragedy

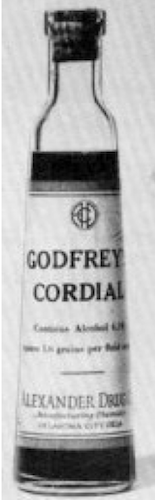

If asked about the use of opium in

Victorian England, some people will think of Limehouse

opium dens and recall the fictional evil Dr Fu Man Chu.

Others will think of De Quincy's "Confessions of an

English Opium Eater" representing the cultured

opium-user indulging in an arcane, secret habit. But few

will have heard of 'Godfrey's Cordial' and other such

widely available narcotic potions.

If asked about the use of opium in

Victorian England, some people will think of Limehouse

opium dens and recall the fictional evil Dr Fu Man Chu.

Others will think of De Quincy's "Confessions of an

English Opium Eater" representing the cultured

opium-user indulging in an arcane, secret habit. But few

will have heard of 'Godfrey's Cordial' and other such

widely available narcotic potions.

In 1850, my

great-grandmother Ellen Cawsey gave evidence at an

inquest which was reported in the North Devon Journal on

7th November 1850. This related to the death of a

Barnstaple baby, Charles Edward Brent, killed by an

overdose of narcotic poison. The mother Caroline Brent

had given her fractious child a dose of "Godfrey's

Cordial" and because the child remained extremely cross,

she was on her way to buy a further pennyworth of

Godfrey's Cordial from Mr Tatham's shop when she met

Ellen Cawsey who mentioned that "Mr. Weeks's stuff was

much better than Mr. Tatham's - that it was more

composing, and quieted the child directly".

Ellen herself gave

evidence, saying "I have a child which is six months

old, and I occasionally give it, when very cross, a dose

of Godfrey's Cordial. In consequence of Mr. Weeks's

mixture.being better than Godfrey's Cordial I have later

had his. When I give my child a dose, it will sleep

soundly for three hours, say from ten in the morning to

one. The child is not dull or stupid afterwards that I

can see".

Opium (in some form) was

the active ingredient of Godfrey's Cordial, of "Mr

Weeks's mixture", and of many other uncontrolled

remedies. Godfrey's Cordial was originally devised by

Thomas Godfrey in the early 18th Century. Though a

bottle did not contain very much opium, the opium tended

to settle to the bottom of the bottle and hence

overdosing was common.

'Weeks', whose mixture

apparently killed the child, was John Weeks, Grocer and

Tea Merchant of Joy Street Barnstaple. Tatham, who sold

the Godfrey's cordial, was John Walkinghame Tatham,

Chemist and Druggist also of Joy Street. And another

interested party was William Avery. He was not only the

proprietor of the North Devon Journal, but he also sold

patent medicines including Godfrey's Cordial and other

opiates. He advertised these in the Journal.

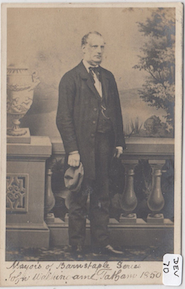

Now John Tatham (left) was

the Foreman of the Inquest Jury - even though he was

obviously an interested party. Perhaps he selected

himself? He was a power in the town, and was just about

to be elected by the Town Council as Mayor of Barnstaple

and Chief Magistrate. (See footnote)

Now John Tatham (left) was

the Foreman of the Inquest Jury - even though he was

obviously an interested party. Perhaps he selected

himself? He was a power in the town, and was just about

to be elected by the Town Council as Mayor of Barnstaple

and Chief Magistrate. (See footnote)

The Inquest Jury led by

Tatham delivered a verdict which attached great blame

'to the party selling such description of medicine' (Mr

Weeks), as well as attaching great blame to the mother.

The North Devon Journal report also led the reader to

believe that the 'Week's' mixture contained 4 drops of

tincture of opium per dose - a very high figure. John

Weeks took issue with this, and wrote a letter published

a week later, insisting that his mixture contained about

1 drop of opium per dose - "two thirds of the strength

allowed by the College".

Cases like this were

widespread - in real life and in contemporary fiction.

Flora Rivers' baby in the Charlotte Yonge novel, Daisy

Chain (1856), was killed by an overdose of Godfrey's

Cordial given for fretfulness by an ignorant nurse.

The North Devon Journal

report itself commented on "the dreadful and dangerous

practice, so prevalent among the working classes, of

mothers accustoming their offspring to noxious doses,

for the purpose of quieting them to rest, and thereby

permitting their parents to be free for other

engagements, practice, we are afraid, exceedingly

common, and which, if not often productive of

immediately fatal consequences, as in the present

instance, must in numerous cases lay the foundation of

delicacy in future life, and probably induce premature

decline and decay.

But it was not until the

1868 Pharmacy Act that the supply of Opium and other

such substances began to be regulated.

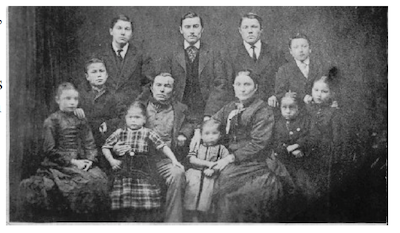

Returning to my Great-grandmother, Ellen

Cawsey, we do not know whether she continued buying

Godfrey's Cordial or other such opiates. We do know that

Elizabeth, the baby she referred to in this case died at

the age of two. But Ellen then went on to have 16 more

children, of whom about 10 lived to be healthy adults.

My grandfather, Thomas, is the small child at Ellen's

knee in this picture of the family.

Returning to my Great-grandmother, Ellen

Cawsey, we do not know whether she continued buying

Godfrey's Cordial or other such opiates. We do know that

Elizabeth, the baby she referred to in this case died at

the age of two. But Ellen then went on to have 16 more

children, of whom about 10 lived to be healthy adults.

My grandfather, Thomas, is the small child at Ellen's

knee in this picture of the family.

Footnote

In the years from 1850

to 1852, the Barnstaple Town Council was riven by bitter

dispute, and William Avery (printer) and John Tatham

were at the heart of it, as was a second William Avery

(woollen merchant, Alderman, and a previous Mayor). This

started with the 1850 contested election of John Tatham

as Mayor. His suitability was not universally agreed.

His friends referred to his honour, strict integrity and

liberal hospitality, and declared that the sword of

justice could safely be placed in his hands. His

opponents suggested that a great number of Barnstaple's

inhabitants were strongly opposed to Mr Tatham. (For

reasons which included the fact that he wore a cap!)

In 1851, William Avery,

the printer and Journal proprietor, was elected to the

Council by a tiny majority over Thomas King, and then

chosen as Mayor to succeed Tatham. Ballot-rigging in the

Council election was alleged, and this led to cases in

the Devon Assizes, in which both the William Averys were

accused. Though it seemed to be a fact that ballot

papers had been stolen, the two Averys, and other

accused parties were found not guilty. William Avery

(printer) remained Mayor, and was also Mayor in several

later years. But the case also led to bitter exchanges

of correspondence between William Avery and Thomas King,

published in the Journal in 1852.

David Cawsey