My Great-Grandmother

My Great-Grandmother

How much do you know

about your great-grandmother? I expect many

of you will know very little except for the family

relationships, and perhaps some old photographs.

One of my

great-grandmothers was Ellen Cawsey, a working-class

Victorian woman. She was illegitimate and uneducated and

she died at the age of 42, nearly 150 years ago. She had

given birth to 17 children! Her life was remarkable,

given the handicaps and burdens, and her short life. So

this is her story - a piece of social history.

I must start by setting

the scene. The Industrial Revolution came late to North

Devon. But in the mid-1820s a large lace factory was

built in Barnstaple, which became an industrial town.

This attracted indigent agricultural workers who

included John and Prudence Casey. It was a good move for

them; John had been declared a pauper in 1827, and the

move to Barnstaple led him to relative prosperity and

assured jobs for his family. John and Prudence had five

sons. They were an unruly family. One son, James, was

transported to Australia - for stealing apples from an

orchard when he was only 14 years old. Three more,

George, William and Robert, were all in court from time

to time for numerous offences, throughout their lives -

mainly disorderly conduct. But the second son, John

Cawsey junior kept out of trouble. So enter Ellen.

Ellen Perryman came to

Barnstaple to work as a servant. and married John Cawsey

junior early in 1850, already expecting her first child

at the age of 18. She was soon involved in a tragedy. At

that time it was common for working women to administer

opium-based sedatives to their fractious babies. Such

medicines were uncontrolled and readily available. Ellen

had used "Mr Weeks' mixture", and recommended it to a

neighbour, Caroline Brent. And that caused the death of

baby Charles Edward Brent, followed by an inquest which

concluded that the mixture contained far too much opium,

blaming Mr Weeks, a grocer. Such poisonings were common

and led to the passing of Pharmacy Acts.

Ellen's own baby,

Elizabeth, did not survive long either, dying in 1853.

Soon after this the cholera pandemic of that period took

many lives in North Devon. (Could life ever be the same

again?). But John and Ellen survived, and by 1859 they

had 5 healthy children, all boys. In that year there was

the first of several incidents which showed that Ellen

was no shrinking violet. I will return to this.

Most years brought yet

another baby! Ever more mouths to feed. But clearly

Ellen managed the family finances well. And in the

indisputably prosperous 1860s 'an affluence came to the

artisanate'. John's earnings as a skilled lace twister

were good and were supplemented by Ellen's earnings as a

bobbin winder, and before long by the wages of the older

boys. And enterprising Ellen started a second-hand

clothes business, publicised by weekly advertisements.

That was clearly profitable. They were able to move to a

larger house further from the factory, and Ellen had a

'servant' - a 14 year-old girl.

But of course this area

was no place for the genteel - and Ellen certainly

wasn't genteel, as we realise from the reports of her

appearances in the magistrates' court. In the 1859 case,

Ellen had been summoned, and we read "Mrs. Cawsey,

having a suspicion that complainant had some hand or

part in casting a foul imputation upon her fair fame,

applied to her certain uncomplimentary epithets, which,

it was alleged by one of the witnesses, Mrs. Cure freely

reciprocated. " Ellen paid a small fine and was

cautioned to be more correct in her deportment in

future. A case in 1871 was very similar, and she,

together with a neighbour, was fined 5/- "for bad

language....... an offence against public morality".

But another case in 1872

was unusual, and local newspaper readers were

entertained by a long report of Ellen's complaint

against her husband, John. We learn that John was

quietly supping his ale in the Union Inn, when Ellen

stormed in, her purpose being to make him "bring his

sovereigns home for the support of the family". She hit

him with her umbrella and broke it. She threw a 'beer

warmer' at him, denting his hat.

His retaliation gave her a frightfully black eye. But

when three women took her out, she struggled to get away

and wanted to go back again. However her complaint was

upheld, and John was fined £1.

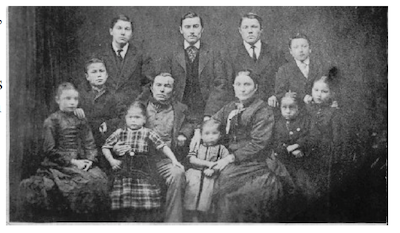

Their normal married life resumed. This

family photograph must have been taken only a few months

after the last incident. My grandfather, Thomas, is the

tiny boy by his mother's knee.

Their normal married life resumed. This

family photograph must have been taken only a few months

after the last incident. My grandfather, Thomas, is the

tiny boy by his mother's knee.

That was life in the

mid-nineteenth century, a time of large families brought

up by hard-pressed parents living in crowded conditions

with no mod-cons and threatened by rampant disease.

There may be similar stories to be told about your

great- grandparents.

Life will never be like

that again. (Or will it?)

(The North Devon

Journal was the source for most of this - and much more.

Almost all copies from 1824 have been digitised and

indexed in the British Newspaper Archive, where a great

many other local newspapers can also be explored online)

DAVID CAWSEY